according to one study, what percentage of females in jail have histories of exposure to trauma?

No escape: The trauma of witnessing violence in prison

A recent written report of recently incarcerated people finds that witnessing violence is a frequent and traumatizing experience in prison.

by Emily Widra, December two, 2020

Early this yr — before COVID-19 began to tear through U.S. prisons — five people were killed in Mississippi state prisons over the class of one week. A ceremonious rights lawyer reported in February that he was receiving 30 to 60 letters each week describing pervasive "beatings, stabbings, deprival of medical care, and retaliation for grievances" in Florida state prisons. That same calendar month, people incarcerated in the Souza-Baranowski Correctional Center in Massachusetts filed a lawsuit documenting allegations of abuse at the hands of correctional officers, including being tased, punched, and attacked past baby-sit dogs.

While these horrific stories received some media coverage, the plague of violence backside bars is often overlooked and ignored. And when it does receive public attention, a discussion of the effects on those forced to witness this violence is virtually ever absent. Nearly people in prison desire to return domicile to their families without incident, and without adding time to their sentences by participating in farther violence. But during their incarceration, many people become unwilling witnesses to horrific and traumatizing violence, as brought to light in a February publication by Professors Meghan Novisky and Robert Peralta.

In their study — one of the first studies on this field of study — Novisky and Peralta interview recently incarcerated people about their experiences with violence backside bars. They observe that prisons accept go "exposure points" for extreme violence that undermines rehabilitation, reentry, and mental and physical health. Because this is a qualitative (rather than quantitative) study based on extensive open-ended interviews, the results are non necessarily generalizable. However, studies like this provide insight into individual experiences and indicate to areas in demand of farther study.

Participants in Novisky and Peralta'due south study reported witnessing frequent, cruel acts of violence, including stabbings, attacks with scalding substances, multi-person assaults, and murder. They also described the lingering furnishings of witnessing these traumatic events, including hypervigilance, anxiety, low, and abstention. These traumatic events affect health and social function in means that are not then different from the aftereffects faced by survivors of straight violence and war.

Violence backside bars is inescapable and traumatizing

Violence in prison house is unavoidable. By design, prisons offer few prophylactic spaces where one can sneak abroad — and those that be offer only a small measure out of protection. Novisky and Peralta'southward findings echo previous research revealing that incarcerated people often "experience safer" in their individual spaces, such equally cells, or in a supervised or structured public infinite, such as a chapel, rather than in public spaces like showers, reception, or on their unit of measurement. However, even inside their cells, people remain vulnerable to seeing or hearing violence and being victimized themselves.

Participants in Novisky and Peralta'southward report discussed graphic, horrific acts of violence they had witnessed during their incarceration: stabbings, beatings, broken bones, and attacks with makeshift weapons. Some participants were even forced into direct, involuntary participation, by being required to clean upwards blood after an set on or murder. "I used then much bleach in that bath … I just couldn't look," one participant recalled. "I only kept pouring the bleach in it [the claret], and pouring the bleach in it, and then I would mop it." Every bit the authors succinctly state, "the burdens of violence are placed not just on the direct victims, but also on witnesses of violence."

Responses to witnessed violence backside bars can result in post-traumatic stress symptoms, similar anxiety, depression, avoidance, hypersensitivity, hypervigilance, suicidality, flashbacks, and difficulty with emotional regulation. Participants described experiencing flashbacks and being hypervigilant, even after release. One participant explained: "I'm trying to change my life and my thinking. But it [the violence] e'er pops upward. I get flashbacks well-nigh it … just how the violence is. In a split second y'all can exist cool. And then the next matter you know, there'due south people getting stabbed or a fight breaks out over nothin'."

The effects of witnessing violence are compounded by pre-existing mental health conditions, which are more mutual in prisons and jails than in the full general public. As 1 participant in the Novisky and Peralta study put it, prison is no identify to recover from past traumas or to manage ongoing mental wellness concerns: "I don't think it [prison house] made my PTSD worse, it but fabricated the PTSD I already had trigger the symptoms."

Violence in prison by the numbers

Prisons are inherently tearing places where incarcerated people (frequently with their ain histories of victimization and trauma) are oftentimes exposed to violence with disastrous consequences. Considering in that location is no national survey of how many people witness violence behind bars, we compiled data from various Bureau of Justice Statistics surveys and a 2010 nationally representative study to prove the prevalence of violence. The table below shows the near recent data available,1 although information technology is likely that many of these events are underreported.

Given the vast number of violent interactions occurring behind bars, as well every bit the shut quarters and scarce privacy in correctional facilities, it is probable that almost or all incarcerated people witness some kind of violence.

| Reported incidents and estimates | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator of violence | Land prisons | Federal prisons | County jails | Source |

| Deaths by suicide in correctional facility | 255 deaths in 2016 | 333 deaths in 2016 | Bloodshed in Land and Federal Prisons, 2001-2016; Mortality in Local Jails, 2000-2016 | |

| Deaths by homicide in correctional facility | 95 deaths in 2016 | 31 deaths in 2016 | ||

| "Intentionally injured" past staff or other incarcerated person since access to prison | 14.8% of incarcerated people in 2004 | viii.3% of incarcerated people in 2004 | Survey of Inmates in State and Federal Correctional Facilities, 2004 | |

| "Staff-on-inmate assaults" | 21% of incarcerated men were assaulted by staff over 6 months in 2005 | Wolff & Shi, 2010 | ||

| "Inmate-on-inmate assaults" | 26,396 assaults in 2005 | Census of Land and Federal Adult Correctional Facilities, 2005 | ||

| Incidents of sexual victimization of incarcerated people (perpetrated past staff and incarcerated people) | sixteen,940 reported incidents in 2015 | 740 reported incidents in 2015 | 5,809 reported incidents in 2015 | Survey of Sexual Victimization, 2015 |

| one,473 substantiated incidents in state and federal prisons and local jails in 2015 | ||||

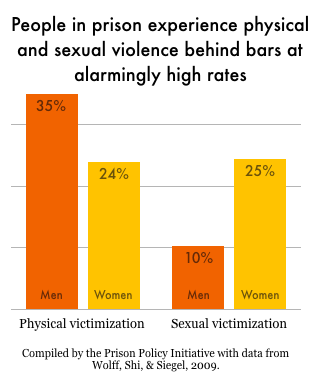

Prison house is rarely the start identify that incarcerated people experience violence

Even before entering a prison or jail, incarcerated people are more probable than those on the exterior to have experienced corruption and trauma. An extensive 2014 report institute that 30% to 60% of men in country prisons had postal service-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), compared to 3% to half dozen% of the full general male person population. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, 36.7% of women in land prisons experienced childhood abuse, compared to 12 to 17% of all adult women in the U.Due south. (although this enquiry has not been updated since 1999). In fact, at least half of incarcerated women identify at to the lowest degree one traumatic outcome in their lives.

The effects of this earlier trauma carries over into people'south incarceration. Most people inbound prison have experienced a "legacy of victimization" that puts them at higher adventure for substance use, PTSD, low, and criminal beliefs. Irritability and ambitious beliefs are besides common responses to trauma, either acutely or every bit symptoms of PTSD. Rather than providing handling or rehabilitation to disrupt the ongoing trauma that justice-involved people oftentimes face, existing research suggests our criminal justice arrangement functions in a style that only perpetuates a cycle of violence. Information technology is non surprising, then, that violence behind confined is common.

The human relationship between by traumas and violence in prisons is further illuminated by a growing body of psychological research revealing that traumatic experiences (directly or indirect) increase the likelihood of mental illnesses. And we know that incarcerated people with a history of mental health bug are more probable to engage in concrete or verbal assail against staff or other incarcerated people.ii

Violence continues later release

The cycle of violence too continues after prison house. An analysis of homicide victims in Baltimore, Maryland, found that the vast majority were justice system-involved, and 1 in four victims were on parole or probation at the time of their murder. Other research has found that formerly incarcerated Black adults are more likely than those with no history of incarceration to be beaten, mugged, raped, sexually assaulted, stalked, or to witness another person existence seriously injured.

"Gladiator school" and ties to PTSD among veterans

While the effects of witnessing violence in correctional facilities have not been extensively studied, Novisky and Peralta's findings are reminiscent of the significant body of psychological research about veterans, witnessed violence, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. And while a prison house is not a war zone, the study participants themselves made these comparisons, describing prison as "going through a nuclear war," "a jungle where simply the stiff survive," "needing to go be ready to go to war constantly," and "gladiator school." Veterans, regardless of exposure to combat, are unduly at take a chance for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and can experience the same debilitating symptoms of PTSD that Novisky and Peralta document among recently incarcerated people.

In an article cartoon attention to PTSD amongst our nation's veterans, announcer Sebastian Junger describes his ain experience with symptoms of PTSD subsequently witnessing violence in Afghanistan. Importantly, he points out that just well-nigh ten percent of our armed forces actually come across combat, then the exorbitantly high rates of PTSD among returning servicemembers are not only acquired past directly exposure to danger.3 The extensive psychological research on witnessed violence among veterans helps u.s.a. better understand the risks of witnessing violence in other contexts; with the findings from Novisky and Peralta's report, we tin can see a similar design of post-traumatic stress symptoms amongst incarcerated people who have witnessed acts of violence, even if they did not participate directly.

Witnessing violence — whether on a neighborhood cake, prison unit, or a battlefield — carries serious ramifications. Exposure to this kind of stress can lead to poor health outcomes, such as cardiovascular illness, autoimmune disorders, and even sure cancers, which are compounded by inadequate correctional health intendance. Previous inquiry has also shown that violent prison conditions — including straight victimization, the perception of a threatening prison environs, and hostile relationships with correctional officers — increment the likelihood of recidivism.

Moving forward

Novisky and Peralta's study should be read as a telephone call for more than research — and concern — well-nigh prison violence. Future research should focus on the effects of witnessed violence on further marginalized populations, including women, youth, transgender people, people with disabilities, and people of color behind bars.

The researchers also recommend policy changes related to their findings. In prisons, they recommend trauma-informed training of correctional staff, assessing incarcerated people to place those most at adventure for victimization, and the expansion of correctional healthcare to include more than robust mental health and trauma-informed services. They also recommend that providers in the reentry organisation receive training regarding the potential consequences of exposure to extreme violence behind bars, such as PTSD, distrust, and anxiety.

While it is important to accost the firsthand, serious needs of people dealing with the trauma of prison violence, the but way to truly minimize the harm is to limit exposure to the violent prison environment. That means, at a minimum, taking Novisky and Peralta's final recommendation to heart: changing the "overall frequency with which incarceration is relied upon as a sanction." Nosotros need to reduce lengthy sentences and divert more than people from incarceration to more supportive interventions. It besides means irresolute how nosotros respond to violence, as we explore in more depth in our Apr 2020 report about sentences for trigger-happy offenses, Reforms without Results.

Vast research with veterans shows that trauma comes non only from direct violent victimization, but can also stem from witnessing violence. Research among not-incarcerated populations further shows that trauma and chronic stress accept a number of adverse furnishings on the human mind and body. And studies washed behind bars prove us that incarceration takes a price on physical and mental health, and that accessing adequate care in prison is a claiming in and of itself. With all of these factors at play and with violence undermining what little rehabilitative effect the justice system hopes to have, we are stacking the cards against incarcerated people.

Source: https://www.prisonpolicy.org/blog/2020/12/02/witnessing-prison-violence/

0 Response to "according to one study, what percentage of females in jail have histories of exposure to trauma?"

Post a Comment